K. Firth/The Record

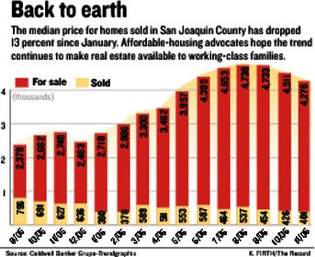

STOCKTON – The median home price in San Joaquin County has dropped 13 percent since January, as free-market gravity took hold of the Valley’s once-booming real estate industry.

But that still is not enough to make owning a home affordable to thousands of San Joaquin County residents.

They still cannot buy a home in an area where the median home price had more than doubled from 2000 to 2004. Such prices mean the average family in the county still cannot afford 95 out of every 100 homes on the market, according to a study released last month.

In 2000, the median – or the midway point between the lowest and highest – price for a home in San Joaquin County was $133,000. By 2004, it had more than doubled to $280,000. At its peak in January, it was $385,000, according to Coldwell Banker Grupe/Trendgraphix.

The high real estate prices, coupled with steadily rising rents across the county, forced more than 20,000 families to seek housing assistance through the San Joaquin Housing Authority in recent years. The big-money climate also limited the amount of affordable housing local governments and nonprofit developers could build.

Now that home prices are sinking each month, working-class families and housing activists are talking about taking back the local real estate market. And some are predicting the floor for prices is a very long way down.

“It’s looking more promising than it has in five years,” said Fred Sheil, who, along with Stockton resident Larry Johnson, builds and rehabilitates homes for local low-income families. “It’s going to come down to where working families can afford to buy a house again.”

His optimism might be strong, but it is shared by few: The county’s median home price would have to drop another 25 percent to reach the $250,000 level that would be affordable to families earning less than $50,000 a year.

Some even believe the housing slowdown will do as much harm as good for poor residents. Bill Mendelson, director of Central Valley Low Income Housing in Stockton, said a cooling housing market could set off a see-saw effect in which rental availability and prices are driven skyward.

“When home sales slow down, more people stay in rental places,” Mendelson said. “Which means there isn’t much movement. They can either hold rents firm or eventually be able to drive them up.”

Many local and state observers expect prices to continue to slide into next year, and that each downward notch is a positive for residents who once thought owning a home was out of reach.

Jerry Abbott, president and co-owner of Coldwell Banker Grupe, said he expects median prices to dip into the range of $314,000 in the coming year.

Those lower prices, combined with interest rates that are expected to hover around 6.5 percent, should make less expensive housing available to families at the county’s median income of $57,100, he said.

“That is something a working-class family can afford,” Abbott said. “That typically would buy a three-bedroom, two-bathroom home. That’ll accommodate most families.”

The real estate slowdown, coupled with housing dollars available through redevelopment programs and other initiatives, allows local affordable housing developers such as Johnson and Sheil’s Stocktonians Taking Action to Neutralize Drugs, or STAND, and Visionary Home Builders of California to increase their output in the community.

STAND built or rehabilitated 72 homes between 1998 and 2001, when houses and property could still be purchased relatively inexpensively.

High speculative values beginning in 2002 cut output by a third, however, because prices had to be raised for the nonprofit agency to break even, Sheil said.

Now that the market is cooling, developers such as STAND say they are back in the game. Vacant lots that sold for $150,000 a year ago have been reduced by one-third, Sheil said, and a growing number of foreclosures caused by rising payments from adjustable-rate mortgages is giving lower-income buyers a bigger and cheaper pool to choose from.

Down-payment assistance programs in Stockton, San Joaquin County and in other local governments should also receive a boost from the real estate slowdown, officials said. Both Stockton and the county have been unable to help as many families using such programs, because the amounts needed for down-payment loans grew nearly eight-fold between 2000 and 2006, according to city and county figures.

Laurie Montes, Stockton’s housing director, said lower home prices might allow the city to spread down-payment assistance loans among more people.

The city also plans to spend $38 million on affordable housing from the city’s Strong Neighborhoods initiative by 2008 and plans to have at least $5 million a year in redevelopment funds after that for such projects.

California voters also approved a bond measure in November that would funnel $2.85 billion into affordable housing projects across the state. It’s still not clear how that money will be divided among hundreds of needy jurisdictions, however.

“It’s all up for grabs,” Montes said. “Every city in California has so many needs.”

There are more than 500 affordable housing units scheduled to be built in Stockton by 2008, Montes said.

But that still leaves the city 9,500 units short of what was called for in its most recent General Plan.

Mendelson, whose agency helps residents with low incomes find apartments, said the cooldown has not reached the rental market.

A study released earlier this month by the National Low Income Housing Coalition echoed that sentiment, reporting that the average renter of a two-bedroom apartment in San Joaquin County needs two paychecks to afford the rent.

Mendelson also does not believe the slowdown in housing prices will spiral back to affordability for the average buyer, saying they have already gone too far to return.

Abbott and others also say prices will eventually settle next year, when the high number of homes flooding the market are reduced.

But Sheil believes 2006 is just a prelude to an even greater decline that will bring real estate back on par with the county’s wages. If and when that happens, Sheil said, fewer people will have to look for help to find a home.

“They’ve run out of people that can afford to buy a $500,000 home,” Sheil said. “Who else are they going to sell to?”

Contact reporter Greg Kane at (209) 546-8276 or gkane@recordnet.com